How do people speak in Berlin and Munich? Is it true that Germans from the north often do not understand Germans from the south? What is the difference between Hochdeutsch and Plattdeutsch? Austrian, Swiss, German languages – what is the difference? When you start learning German, you’re faced with a lot of questions like these. In today’s article, we help you get to grips with the German dialects.

A glimpse into history

In Germany, a relatively small country, there are so many dialects and regional variants that you wonder how Germans understand each other at all. In fact, Germany’s linguistic situation is largely due to historical preconditions. The boundaries of the dialects and regional variants correspond to the boundaries of the early and middle German feudal principalities and associations.

Almost two thousand years ago, in the first or second century, the area of modern Germany was populated by diverse peoples and tribes who were continuously at war with one another and sought to invade new territories. Tribes migrated from south to north and settled above the Alps as a part of the so-called “Great Migration of Peoples,” taking their language and dialectal variations with them. The Alemannen, Bayern, Schwaben, Thüringer, Hesse, Franken, Sachsen, and Friesen were the main tribal groups at the time.

As time went on, the boundaries of the principalities and political entities changed – for example, the area formerly inhabited by the Alemanns is now home to Baden-Württemberg, western Bavaria, western Austria, part of Switzerland, the Principality of Lichtenstein and a small area of modern-day France bordering Germany – Alsace.

Areas of dialect distribution

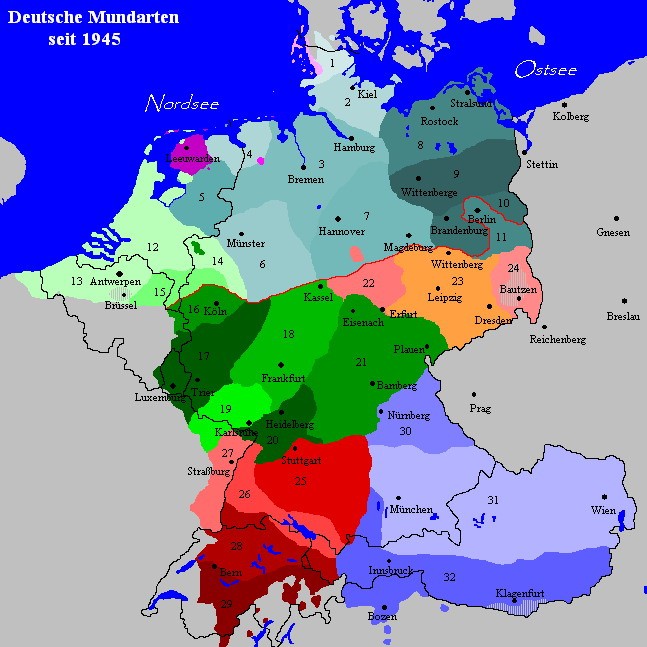

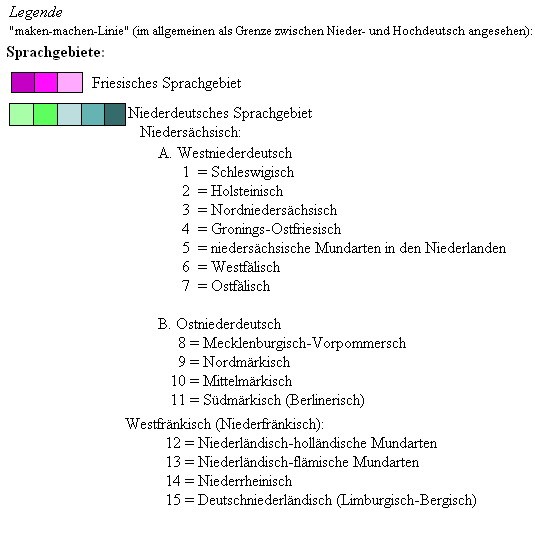

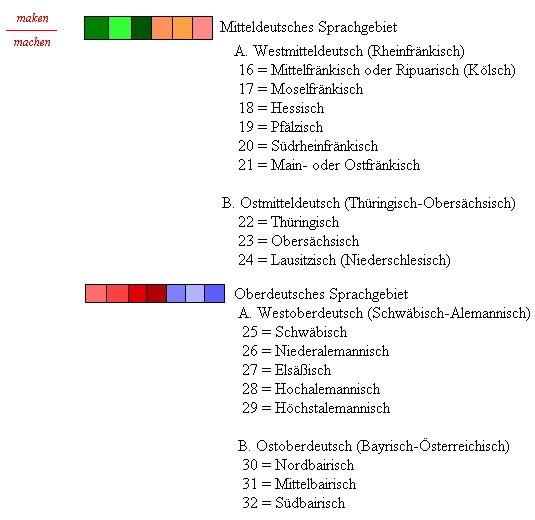

Germans living in the south today, however, can understand each other with far less difficulty than if a Berliner were trying to understand a Munich resident. Dialectal differences in a language reflect, above all, the territorial affiliation of its speaker. The map below shows the main areas of dialect distribution: in red and blue are the Upper German dialects (Bavarian, Swabian, Alemannic, Austrian etc.), in green and orange are the Middle German dialects (Thuringian, Hessian), etc. The exact transcription can be found immediately below the image.

A little history can help you understand how the linguistic varieties in northern and southern modern Germany vary. The so-called “consonantal revolution” was triggered by the Great Migration of Peoples. This linguistic phenomenon’s boundaries can be mapped along a line that crosses the Rhine River at Benrath, south of Düsseldorf. An hypothetical line drawn on the Oder between Düsseldorf, Magdeburg, and Frankfurt would allow a distinction to be made between southern and northern German dialects. Surprisingly, the southern German dialects are referred to as “Upper German,” while the northern dialects are referred to as “Lower German.”

You can question why lower German dialects are present in the north but not in the south. The northern half of Germany is flat and lowland, thus the name “Low German,” while the southern part is mountainous and upland, hence the term “Upper German.”

How do the dialects differ?

In southern Germany, “sch” is often used instead of “s.” The Swabian dialect and pronunciation of the people of Reutlingen, Tübingen, and Konstanz – the region south of Stuttgart – are particularly noteworthy.

Was machst (machscht) du heute? Kannst (kannscht) du mir bitte helfen? Hast (hascht) du es schon?

It is also common to use the diminutive suffix <-le> in this context: Spätzle, Grüßle, Peterle, Leckerle. The <-li> suffix is popular in Swiss German, as in Grüßli, Züri, and Müsli. While the word Müsli has been so rooted in our vocabulary that we sometimes use it without realizing it was once a dialect: a Swiss doctor came up with an alternative way for his patients to eat healthily, and thus the name muesli derives from the word Mus – mashed fruit – in the Swiss variant with our favorite suffix we get Müsli.

In Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, muesli is always greeted with a “Grüß Gott” rather than the normal “Hallo,” and the younger generation will say “Servus.” By the way, we’ve previously written about the various greetings in German. Southern Germans have a distinct intonation that varies slightly from that of northern Germans. After about a month of living in the Stuttgart area, you begin to hear dialect terms and imitate the intonation.

It’s easy to spot the citizens of Cologne and the surrounding area by the way the <ch> is pronounced, as in lustig, komisch, regnerisch, schmutzig: everything sounds the same at the end of the word.

Moving further north, you encounter people pronouncing the “s” at the end of a word as “t”: dat – “das”, wat – “was”, diet – “dies”, allet – “alles”.

The Berlin dialect stands out with its famous ick (ich) and dat (das): Dat kann nit war sein, ick bin doch in Berlin oder wat?

Dialects are commonly used in daily life in Germany, and Germans openly turn between dialect and literary language (Hochdeutsch). Radio and television announcers talk in Hochdeutsch, books and newspapers are printed in Hochdeutsch, plays are staged, and films are produced in Hochdeutsch. It is also possible to turn to a dialect to produce a certain outcome, such as if the protagonist is from Bavaria and his voice emphasizes this. Only Hochdeutsch is used in official documents.

Some dialects are “stronger” than others – they are also used by young people in their communication environment. Do not confuse dialect with slang! You can read about German youth slang in our earlier article. Recently there has been a tendency to pay more attention to the dialect.

You often hear stories like: “A well-known sales representative from Bosch Stuttgart once gave a new product launch in Hamburg, and tried his best to speak in Hochdeutsch during the presentation, which made him lose his train of thought and spoke a lot of “Swabian” intonation. And because of this the presentation was not very successful. But during the dinner our Swabian was not ashamed of his dialect and even made many jokes about it, and everybody agreed that if he had spoken during the presentation the way he was used to speak before, the success would have been guaranteed.

You don’t have to be afraid to speak in dialect, you don’t have to be afraid of suddenly not understanding the dialect – Germans know how to speak both ways. And knowing some dialect forms and vocabulary will allow you to shine in the company of Germans with an extensive knowledge not only of the language, but also of cultural peculiarities.

1. Bayrisch

2. Plattdeutsch

3. Schwäbisch

4. Hamburgerisch

5. Kölsch

6. Fränkisch

7. Österreichisch

8. Ruhrpott

9. Hessisch

10. Berlinerisch

11. Schweizerdeutsch

12. Badisch

13. Pfälzisch

14. Saarländisch

15. Sächsisch

16. Kurpfälzisch

17. Thüringisch

Do you want to get your German language learning planner?

Dive into a World of German Mastery with Leo. Over 7500 enthusiasts are already unlocking the secrets to fluency with our tailored strategies, tips, and now, the German language learning planner. Secure yours today and transform your language journey with me!